My Road

15.01.2025

9 min read

Thoughts

We Are In The Same Boat Now

-webp(85)-o(jpg).webp?token=85f327099724759a4d6accf2f2d8cf32)

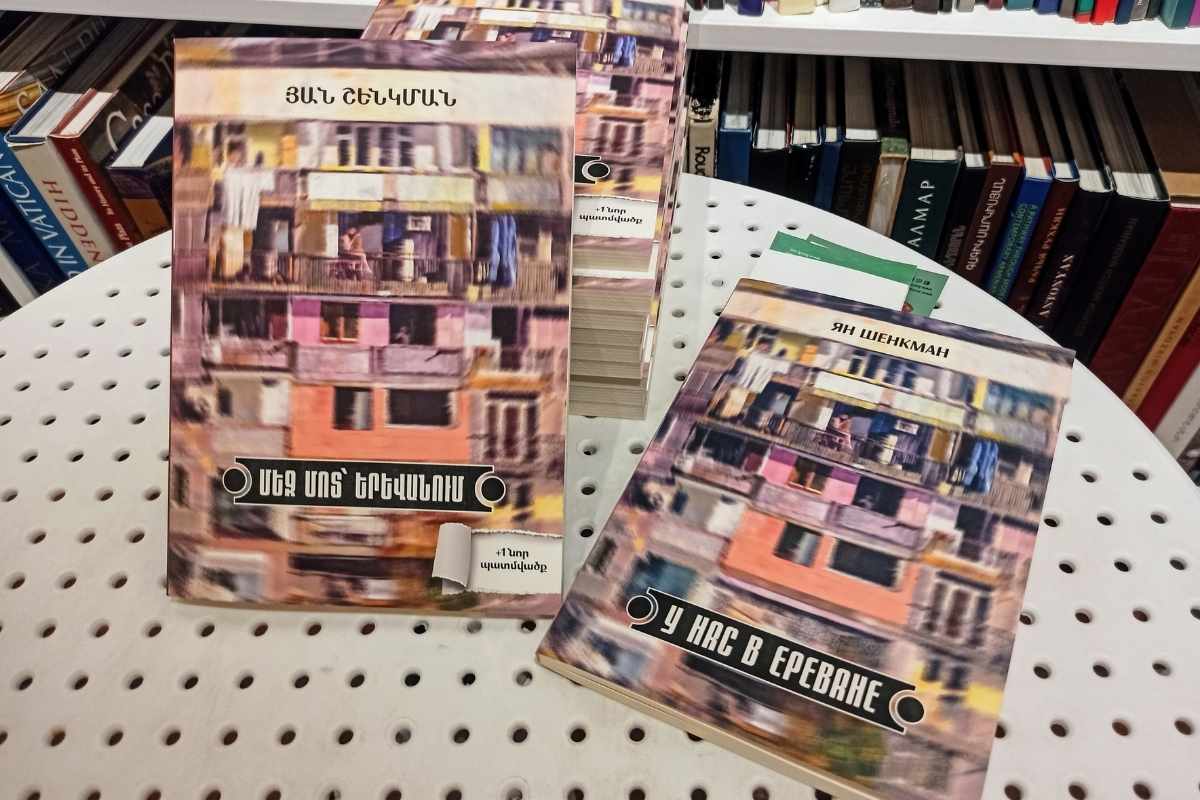

Yan Shenkman, a journalist, writer, screenwriter and host of numerous projects, moved to Armenia during the first wave of relocations in the spring of 2022. Unlike many others, he chose to stay. While some refer to him as a "relocant," Yan prefers to identify as an emigrant. Although his time in Yerevan has been relatively short, he has quickly become a familiar face in the city. Yan is also the author of ‘In Our Yerevan’, which was published in Russian in March 2024 and recently translated into Armenian by the ARI Literature Foundation.

Before coming to Armenia, Yan lived in Moscow, where he worked as an independent opposition journalist and activist. His professional stance, along with his anti-war views, made staying in Russia increasingly difficult.

Photo by Artem Mikryukov

I spoke with Yan about his decision to settle in Armenia, his perspectives on the country, his creative work, and his recent book, which has resonated with readers in Yerevan.

On “Relocation”

“Most of us, after the war began, weren’t so much coming to Armenia as fleeing Russia. This included many Russian Armenians. People came here to catch their breath, reassess and decide on the next steps. For many, Armenia was simply a stopover a stepping stone for visas to the West. Only a tiny fraction actually planned to stay for the long term.

The mass emigration to Armenia was largely driven by the fact that the country felt ‘accessible’: a former Soviet republic where Russian is widely spoken and hostility toward Russians is not widespread. Its Christian heritage also appealed to many. And, unlike Georgia, Armenia offered easy entry from Russia without the risk of being turned away.”

Georgia? No. Armenia? Yes.

“I originally planned to visit friends in Tbilisi, but the airfare was higher, which mattered since I was short on money. Just before my trip, I heard about a prominent opposition journalist being denied entry into Georgia, and I didn’t want to risk the same. So I flew to Yerevan, thinking I’d travel to Georgia overland. But when I arrived, I thought, ‘Why leave?’

In Yerevan, people often ask me, ‘Are you an IT specialist or just here on vacation?’ I always reply: ‘I live here.’

The first months were tough. A sudden, forced relocation is always stressful. I lived in a tiny, shabby room in Shengavit with no clear prospects and a low mood. But I accepted my circumstances – there was no point lamenting lost status, money or opportunities. For me, there was no initial euphoria or disappointment – just immediate acceptance. I even prepared myself for the possibility of washing dishes in a café to get by. Survival was the priority, and I was willing to do whatever it took.

Thankfully, Armenian journalists and human rights activists supported me. Two months after my arrival, I was offered the role of editor-in-chief for the Russian version of Alik Media. Though I didn’t stay there long, it was my first job in Armenia. I also contributed to European and Israeli media and wrote scripts for various projects. By the summer, I had nearly severed all professional ties to Russia. It’s been so long since I’ve handled Russian rubles that I’ve forgotten what they look like.”

Fruits of publicity

“From the beginning, I made a deliberate choice to stay visible. I didn’t hide or keep quiet. I spoke openly about Russia, emigration and events in Armenia. This openness brought interviews and opportunities.

In the spring of 2023, Armenia’s oldest TV channel, Noyan Tapan, approached me for a collaboration. This led to my show, Displaced Persons, which delved into the ongoing mass migration wave. The program aired twice a month, featuring conversations about the immense global shifts we’re witnessing – changes no one fully understands yet.

The audience was mainly Armenian, while the guests ranged from politicians and artists to ordinary people rebuilding their lives in a new country. We discussed war, peace, loss and hope.

One memorable episode featured political scientist Edgar Vardanyan, where we explored the enduring imperial mindset of some Russians who’ve moved here. Another, with Vartan Marashlyan of Repat Armenia, examined "the identity struggles of Russian Armenians torn between Armenia and the Kremlin." After that meeting, Vartan said: "It’s great to see new platforms emerging in Armenia for exchanging ideas and engaging in conversations – not just in the traditional format where Armenians speak and Armenians listen, but also where relocants, immigrants and people from various backgrounds have their say. Political emigration may still be uncommon, but it’s an important process. People who move for political reasons often become key drivers of change in their new countries, offering fresh perspectives on issues that matter for Armenia."

A year later, this project transitioned into a live format, becoming a lecture series. We met at Tumanian’s Art café, relocated from Stepanakert to Yerevan, and explored a wide range of topics – from Armenian music history to neo-colonialism.

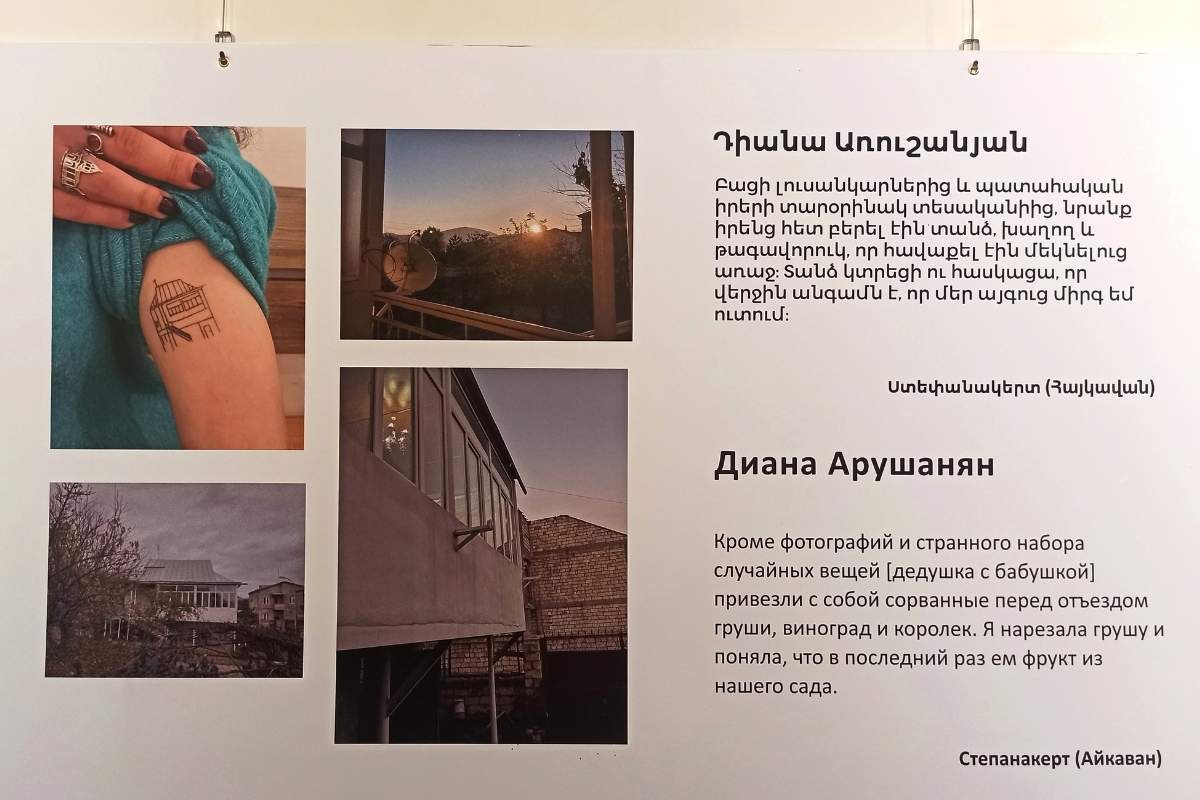

On Addressing the Trauma of Artsakh

“Displaced persons" is not the only project Yan has worked on in Armenia. In early 2024, Yan organized an exhibition titled “My Home in Artsakh” at the Tamanian Museum-Institute of Architecture. It featured photographs of abandoned homes and monologues from their displaced residents.

“When the Artsakh crisis erupted in September 2023, I struggled to find a way to contribute. Volunteering wasn’t my strength, and media coverage wasn’t working out. Even at the start of the blockade, I tried to raise awareness both here and in European media, but no one was interested. This is one of those cases where it's not the journalist who should be speaking, but the people directly involved, the people who have been displaced. Early on, I realized the central theme of this tragedy wasn’t ‘war,’ ‘ethnicity,’ or even ‘land’ – it was ‘home.’ I wanted people to share their stories of home.

Photo from the exhibition "My Home in Artsakh." By Zhenya Yengibaryan.

The goals were simple: to preserve memories, help process trauma and make people feel seen. While it had an impact, one or two events alone aren’t enough. For meaningful change, we need hundreds of such initiatives sustained over time.”

Jan had previously covered the issue of Artsakh. In the summer of 2022, just before Berdzor fell, he traveled to Artsakh and produced a detailed report on the surrender of the Lachin Corridor.

– That’s when I started to grasp what was going on: how people were living and the role the peacekeepers were playing in all of it.

Later, in January 2024, Jan released his film The Karabakh Tragedy: Surviving Without a Homeland, which told the stories of the deported Artsakh people.

Living in Armenian Armenia

“As an outsider, I sometimes notice things locals might overlook. Many Armenians seem defeated, as if they’ve lost hope in their country’s future. But that’s not true. This is a place where people from all over the world come to work and build businesses. If you talk to some of the Lebanese here, many consider Armenia a paradise. There are certainly countries in much worse shape.

People often ask me about the pros and cons of life here. It’s not an easy question. Right now, I’m in a mindset where the advantages of Armenia are slowly becoming the disadvantages. A lot of us, immigrants, had this idealistic but politically misguided thought: if we can’t make Russia a normal country, let’s build this "normal Russia" somewhere else, where we can have everything we love, but not under the Russian state. The idea played out like this: we come to Armenia, there's no Putin-style oppression, everyone speaks Russian, and life is familiar. Let’s set up the same kind of business we had in Russia, keep the same kinds of entertainment, bring in the products we miss. And so on.

But the reality is that you can't just bring the good parts and leave the bad ones behind. You try to build this "other Russia" here, but it inevitably turns into the same one we left behind. The good and bad are so closely linked that you can’t separate them.

Of course, this is "emigration light." Here, I meet people I can have great conversations with about Russian literature, and they understand it just as well as those I spoke with back in Moscow. Many don’t need to be explained the ins and outs of Russian life – they’re already aware. But for me, there’s no need to keep seeing the same things at every turn. Sometimes it physically bothers me. I can’t decide if I’ve really left Russia or not. Sometimes I think: maybe I should’ve moved somewhere completely different, somewhere with no connection to Russia, and started a whole new life.

Photo from the book presentation ‘In Our Yerevan’. By Zhenya Yengibaryan.

I love Armenia and the Armenians, but it bothers me how much Russia’s presence is still felt here – not just politically, but mentally, in everyday life. I wish I could live in a fully Armenian Armenia, not a semi-Russian one.

"I’m incredibly lucky with the country. I consciously didn’t go to Europe, knowing there would be problems and mental isolation. And I was right."

Of course, life is better here. Armenians communicate very gently, without aggression, which makes for a comfortable atmosphere. They help each other out, especially newcomers, even though they’re struggling themselves. They’re kind, open people, but there’s a sense of ambivalence – good things can quickly turn into bad things. I get the feeling that, despite their amazing moral qualities, Armenians are just not ready to fight back against evil. They’d rather endure it. The country is beautiful, but unfortunately, it’s completely defenseless.

On Losses and Gains

– For now, I've found my niche: I write and talk about those who’ve left, not just from Russia. This is something I understand very well. I believe I have the moral right to cover this topic. But when it comes to Russia, I write about it less and less. It wouldn’t be honest. You have to actually be there to truly write about it and do it justice.

Yes, I lost stability and security, but strangely enough, I’ve even gained financially. In Moscow, I worked for embarrassingly little money. But the most important thing is that I now live a completely independent life. All the responsibility is on me, and I make every decision myself. And this is also a feature of Armenia: this country isn’t for people who prefer to settle into a big corporation and slowly climb the career ladder – there’s almost none of that here. But for those who are constantly initiating something, it works. As Vartan Marashlyan says, Armenia is a country of startups. I agree with him. Yes, it’s tough. And, let’s face it, the standard of living in Armenia is lower than in Europe or Moscow, and overall the situation is unstable. But there are things that matter more to me.

In the Same Boat

– We all face serious risks: the risk of Azerbaijani aggression, the risk of pressure from Russia, the risk of deportation, the risk of a pro-Russian coup. But these risks are shared – if war breaks out with Azerbaijan, we (the émigrés) can’t pretend it won’t affect us. If Russia’s Federal Security Service comes here with punitive intentions, it won’t matter which passport you hold – Russian or Armenian. Everyone will suffer.

Our fate is now tied together. We either survive together or perish together.

‘In Our Yerevan’ or Illusions and Failed Escapes

Photo from the book presentation of "In Our Yerevan." Author: Zhenya Yengibaryan.

“I have nowhere else to run, and I don’t plan to,” wrote Yan in his book In Yerevan with Us.

By the way, some people unfamiliar with the author criticized him for the “imperial” tone of the title. But Yan wasn’t offended – he understood.

This is Yan’s seventh book and the first one translated into another language.

– Finally, I’ve been translated into a foreign language. But actually, I write in a foreign language, and they’ve translated me into the one I should be in –the language a book about Yerevan, emigration, and war should be in.

“You wanted to live in the beautiful Russia of the future? Well, we’re already living in it, and that’s a plus. But it’s not Russia, and that’s a minus.”

This book is full of light, pain and a great deal of humanity and love. It was bound to succeed and no wonder it made it into the top 5 bestsellers in the largest Yerevan bookstore chain, Bukinist. Yan himself categorizes it as autofiction – a pseudodocumentary based on real events. When asked, “What is the book about?” he answers succinctly: “About a failed escape.” And he adds, “It seemed like there was a better life somewhere, one you could escape to. But that was an illusion. What’s happened to us in the last few years has shown that the world is one; there’s nowhere to run. It’s time to live.”

Interviewed by Zhenya Yengibaryan

This publication includes quotes from the book 'In Our Yerevan’

-

News

-webp(85)-o(png).webp?token=1c587df7df6ef4a8e220e5ea824554b9) 09.01.2026Short-Term Return: How Diaspora Armenians Can Contribute Without Moving Fully

09.01.2026Short-Term Return: How Diaspora Armenians Can Contribute Without Moving Fully -

Armenian by Choice

-webp(85)-o(jpg).webp?token=67c1ef9733155840058be1c3cf71a754) 19.12.20248 min readThe Golden Vine House: A Crossroads of Past and Present, Armenian and Basque

19.12.20248 min readThe Golden Vine House: A Crossroads of Past and Present, Armenian and Basque

-webp(85)-o(jpg).webp?token=b1cb111a56e1834ffd8f0229030f8815)

-webp(85)-o(jpg).webp?token=35bc085be51a8c3206a26e1725b41703)